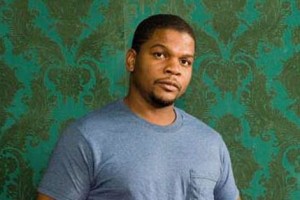

The public perception of black male youth has arguably changed since artist Kehinde Wiley began painting his formal portraits while in residency at New York’s Studio Museum in Harlem in 2000. Part of Wiley’s process was lifting his subjects straight from the street and rendering them-complete with sneakers, track pants, tank tops, and team caps-in the visual language of classic European portraiture; the result wasn’t so much brashly iconoclastic as brilliantly inclusive, a mash-up of museum treasure and the urban life outside of its gates. What remains so surprising about these works today is that the 31-year-old Los Angeles native’s black males remain a rarity in the fine-art world, despite their prevalence, even dominance in pop culture. Wiley may have redefined portrait painting for a new century, but he’s still cutting his own path in a field that purports to be progressive.

The public perception of black male youth has arguably changed since artist Kehinde Wiley began painting his formal portraits while in residency at New York’s Studio Museum in Harlem in 2000. Part of Wiley’s process was lifting his subjects straight from the street and rendering them-complete with sneakers, track pants, tank tops, and team caps-in the visual language of classic European portraiture; the result wasn’t so much brashly iconoclastic as brilliantly inclusive, a mash-up of museum treasure and the urban life outside of its gates. What remains so surprising about these works today is that the 31-year-old Los Angeles native’s black males remain a rarity in the fine-art world, despite their prevalence, even dominance in pop culture. Wiley may have redefined portrait painting for a new century, but he’s still cutting his own path in a field that purports to be progressive.

Wiley’s practices have changed in the last decade and the results are increasingly visible. His recent show at the Studio Museum in Harlem called “The World Stage” took him all over the globe, from Lagos to New Delhi, to cast his models from the street and capture them in poses representing a larger world. His solo exhibition “Down” opens at Deitch Projects in New York City this month; “Down” features eight large-scale paintings of black youths based on iconic images of fallen warriors in art-from bullfighters to Christ. Here he talks about his work with his friend, fellow sampler, and pop star M.I.A. She managed to get stung by a bee during the interview, but the two still got around to tackling the demise of hip-hop and the death of the New York art scene.

M.I.A.: I wanted to ask you about the progression of your work these days. How are you finding it? Because New York is a really different place to make art compared to what it used to be.

KEHINDE WILEY: I came here almost 10 years ago now. It was my first experience of making a life for myself outside of school, and my career kind of snowballed at once. So there’s really not much in the way of an alternative experience for me to contrast it with. These days I’m spending quite a bit of time on the road, which finally has allowed me to get some perspective. I’m starting a new project where I open up studios in different nations and do street casting. I just got back from Brazil and Nigeria and Senegal. Actually, tomorrow I’m leaving for New Delhi.

M: Does leaving New York change your art?

KW: That type of process becomes the work in many ways-physically removing yourself from what your work was based on before. By and large what I’d been doing was mining the streets of African America, using a sort of urban vernacular. That changes radically when you remove yourself physically, especially around the world.

M: Manhattan seems pretty developed, you know what I mean? Like it has peaked in culture. The Village Voice called it McHattan. It’s just become impossible for young, creative artists to live in New York.

KW: Where do you find it most fruitful to work?

M: I think traveling really helps. I know some musicians who have studios in Trinidad. There’s a collective of artists and painters there now who went to Central Saint Martins College [in London] with me. They live there and make art. It’s neat to see that-[people] not led by money or pretentiousness. It’s a small community, but you really have the space to observe and digest the culture. You go to a place where social commentary is rare and important and you can serve people. That’s what’s inspiring to me-finding someplace where people haven’t already seen themselves in a certain light.

KW: Yeah, I know.

M: You create that light, you create that visual or image.

In America, everything has been done. We’ve had everything. And now we’re rerunning what’s already been done.

KW: Right, recycling. The recycled object.

For complete report visit interviewmagazine.com

I have always been a big fan of his work!! JUst so talented! I luv my naija people!